9The Gulf Stream – Almost dying, from Adams perspective.

Lesson learned: Sleep is part of the preparation. While I’m used to odd hours and long shifts, the utter fatigue that sets in when the sailing gets lousy can be mentally and physically incapacitating; leading to poor decision making, procrastination of crucial tasks, even confusion that can lead to steering a wrong course or misinterpreting lights.

Lesson learned:

There is never a good reason to cross the Gulf Stream north to south with winds from the NE. Never. It’s not just rough and choppy. It’s rough, choppy, and no matter the vessel – potentially dangerous. Wait for better weather. For example, just after cold front passage when the winds shift and lighten up. The Gulf Stream is roughly 45 miles wide and flows WSW to ENE through the straights of Florida. You will be feeling its effects for over half the trip from key west to Havana. A wind directly opposite this 1-2.5kt (nearly 1/3rd of your sailing speed) current creates such unrest in the sea state that it virtually guarantees one of the roughest rides you can experience, regardless of the NOAA forecast for reasonable wave heights etc.

Hind sight being 20/20, did we, as a crew, make the right decision to press on? I’ve thought long and hard about it. Knowing what I know now, I would have personally advocated for delaying our departure given the same or similar circumstances. However, that being said, I feel like sailing can be summed up best in the sentiment of a short story about camping by author Patrick McManus titled, “A Fine and Pleasant Misery,” in that we only cherish those experiences that were seemingly quite rude to us at the time. Remember the times everything went perfect? No, not really. Remember the times you overcame and conquered? Absolutely.

Lesson learned:

Equipment checks – the best defense is a good offense, EVERYTHING must be prepared before hand, you will find it simply impossible to rig or re rig anything when that time comes. If it is not readily available and ready to use, you may as well leave it at the dock. Unless you can do it with your one free hand during a one handed push-up, it MUST be done before setting off. Oh, we most definitely had all the equipment, just no hope of using it.

I don’t get sick often and I don’t get sick easily. I’ve been seasick before, and I’ve had food poisoning before. I’m going to solidly rate this as a combo malady. Taco Bell before sailing next time? Nope, not for me! If food vendor choice was the major ingredient, the twisted angry sea state was most definitely the major catalyst. Independently, my normally high constitution for these things would have prevailed over either of these obstacles. Unfortunately for me…..

This may be worth mentioning for those that are curious – we were armed with two separate forms of electronic charts (OpenCPN, and Navionics) as well as paper charts for redundancy. The Navionics proved to be accurate, OpenCPN is amazing but crashed irreparably (Android version), and the paper did exactly what they were intended to do….. take up a small amount of space and look pretty. I’ve been running the electronic versions on an ASUS Zen tablet which, FYI, has a true GPS radio that doesn’t rely on cellular or Wi-Fi coverage to get a fix. This is important if you are considering a similar setup.

Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.

“There’s an old saying in Tennesse, I know it’s in Texas, probably in Tennessee that says, ‘Fool me once, shame on … shame on you. Fool me… You can’t get fooled again!'” – President Bush

My faith in NOAA forecasting and GRIB data is slowly dwindling. Don’t get me wrong, they use some sophisticated weather modeling along with buoy data and atmospheric conditions to create a product that is well worth a look. That being said, the more I sail, the more I notice that the wave forecast always seems inadequate or understated in open water. After giving this problem a fair amount of thought and even better, a fair amount of research, I have come to a few conclusions.

Some will say experience is the collection of life’s problems which fail to kill you; that learning happens when you succeed in not repeating mistakes. Let me be your martyr in this case and try to learn from my (and I do take personal responsibility for this as I accept the duty of captain) mistakes.

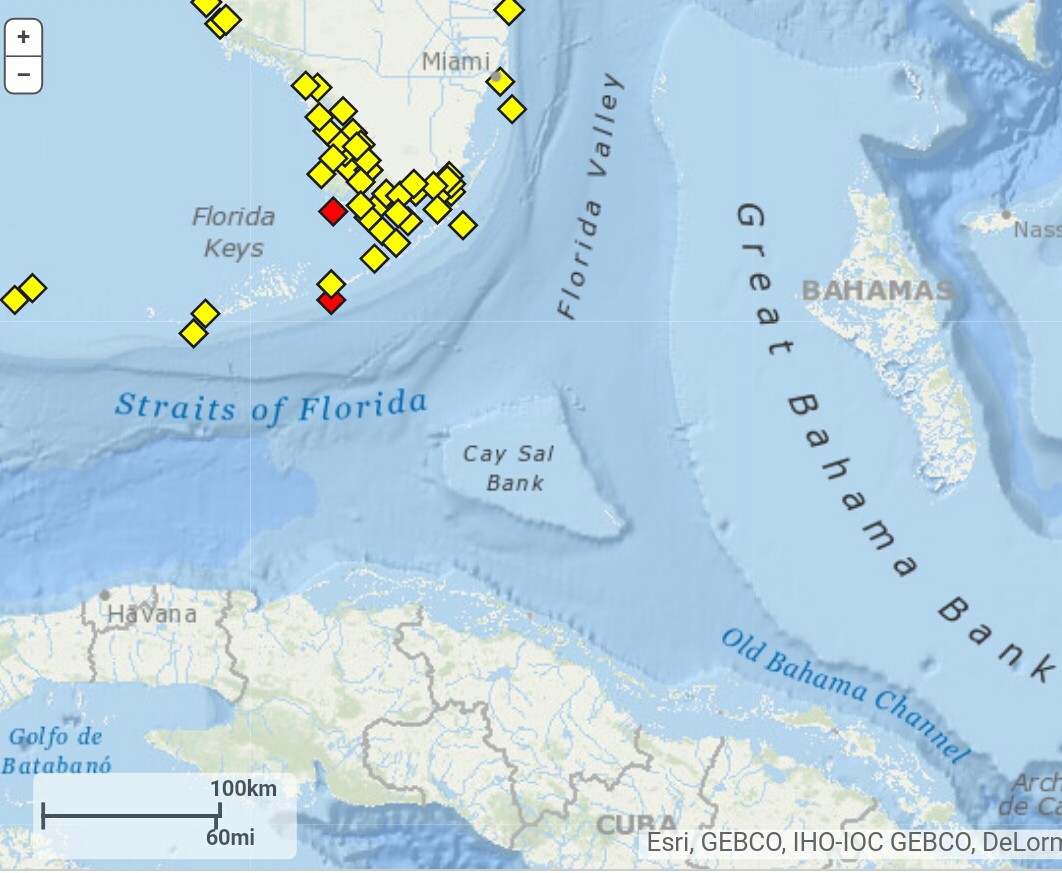

As you can see beyond Key West there are very few (okay, zero) buoys on the way to Cuba. This in and of itself is not a major issue but food for thought. It would be nice to snag some real time data from a buoy in the middle of the gulf stream.

Image from NOAA.gov

Data buoys from Key West to Havana

Let’s take a second and talk about something called fetch – not just a game to be played with your doggy, Barky McBarkerson. Fetch is essentially the distance that waves have to build over time. Given a steady amount of wind blowing over an unlimited distance of open water, waves will build to a maximum height in relation to a quadratic formula. The picture below gives a rough idea of what happens as waves build off shore.

Effect of wind on waves over distance (fetch)

Image from http://homepages.cae.wisc.edu/~chinwu/

The graphical depiction below gives you a quick method of calculating the expected maximum wave height based on fetch distance, and wind speed, with a correction for time that the winds were blowing.

Wave height based on fetch length, wind speed, AND time.

Take our voyage to Cuba as a case study. The winds were blowing from the NE at 15-20 knots and the last natural obstruction was the Bahamas nearly 200 miles away. The winds had been consistent in both speed and direction for nearly 4 days leading up to departure. To use the chart above, follow the fetch distant of 200 up to the 20kt line, then to the right for time in hours (maximum in this case) and you will come up with a solution of 2.5 meters. Multiply by 3.3 to convert to feet and you come up with just over 8′ seas. This is a FAR cry from the forecast 2′ – 3’ seas. Remember also that it will take some amount of time for this height to be achieved, and likewise, it will take some amount of time for the conditions to dissipate when the winds calm or change direction.

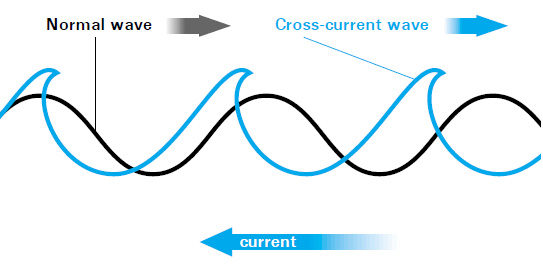

There are many factors which affect not only wave height, but also wave shape. Wind speed and direction, current speed and direction, and water depth, all become factors. Similar to how a wave breaks approaching shallow water, our waves were becoming tall and peaky due to the wind driven waves running almost direct opposition the gulf stream current.

What happens when wind driven waves oppose the current.

Image from ec.gc.ca/meteo-weather

Lesson learned: start watching the weather at least a week out, every day. Look not only at the forecast but the reality of what’s happening. Get an idea of how much wind speed there is, for how long, in which direction, and over what distance of open water. Try to make your own forecast. Look at the marine forecast and at least double the prediction for wave height…. Because in reality, that might be much closer to what you will experience out there in the wild. The gulf stream isn’t civilized and can play some mean tricks. Be safe out there!!

I give credit to my beautiful loving wife for asking me what the actual conditions were that we experienced on our way to Cuba. It got me thinking, thinking got me researching, and researching got me answers to questions I didn’t even realize I had until I started thinking. What a vicious cycle.